【Perspective】 “wetting” provides various physiological functions in cells by governing interactions between phase separated droplets and membranes

WRHI Newsおすすめ

Published online

(Cell Biology Center / Dr. Alexander I. May)

“Intracellular wetting mediates contacts between liquid compartments and membrane-bound organelles”

J. Cell Biol. (DOI:10.1083/jcb.202103175)

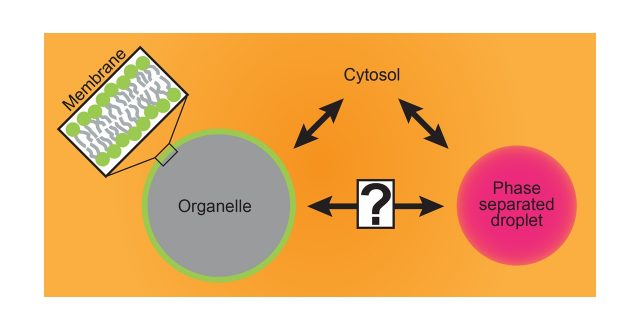

In this paper, May and colleagues contend that a range of subcellular phenomena can be explained using the physical concept of ‘wetting.’ In particular, the authors describe how interactions between phase separated protein droplets and cellular membranes results in morphological and function changes to membranes as well as the droplet. This paper challenges the common conception of phase separated droplets as standalone structures in cells, hinting at a raft of new phase separation-mediated, physiologically important droplet functions.

For details, click here

<Abstract>